Shobini Iyer

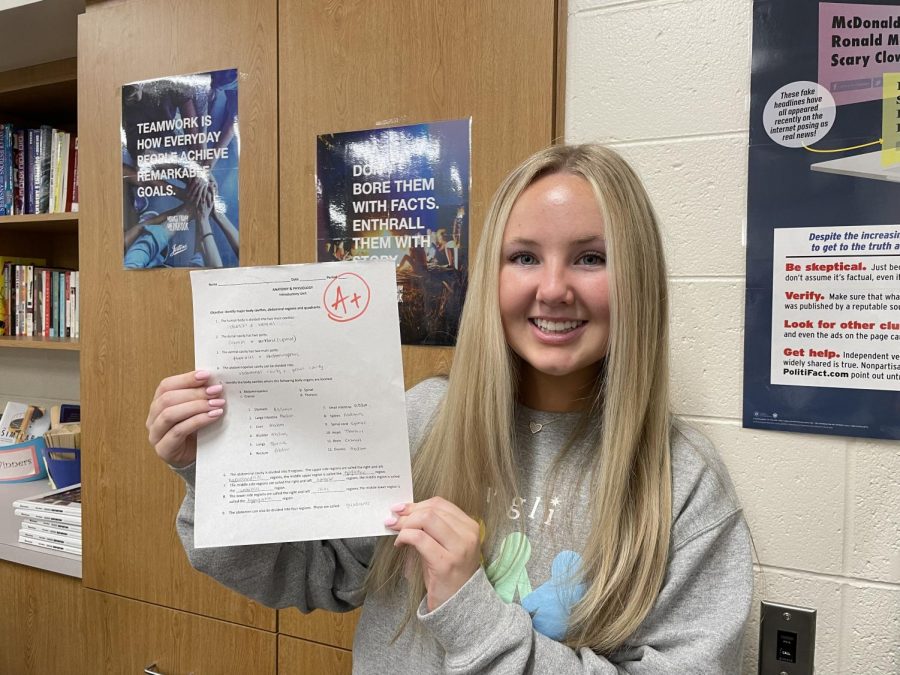

Straight-A student senior Jillian Keppy proudly displays her exemplary grade.

Getting good grades, long considered a fundamental part of high school academic success, has exacerbated into an epidemic running rampant for years: straight-A student syndrome.

Straight-A student syndrome is the obsession with excelling in education at the expense of the education itself. The symptoms are seen on an everyday basis: students frantically copying down lecture notes, seeking out every extra credit point and declining invites to cram for an exam instead. These habits are all defining characteristics of the cookie-cutter straight-A student.

Grades are undoubtedly critical indicators of a student’s work ethic. They motivate students to perform well in school and open doors to post-secondary opportunities—but striving for perfection has its pitfalls.

Academics have turned into an undeclared rat race, which has had crippling effects on teenagers’ mental health. School counselors, teachers and parents alike hold high hopes for students to be high-achieving. A 2019 Pew Research Center study reported that 61 percent of teens aged 13-17 felt tremendous pressure to receive good grades. Rather than setting students up for success, schools and parents have burdened students with insatiable expectations.

For many high schoolers, prioritizing straight-As often correlates with sacrificing extracurricular activities. But this takes away from the primary purpose of high school: to prepare students for the real world. When students abandon hobbies to focus on school, they are inadvertently cheating themselves out of the real-world practice of work-life balance.

So what is the antidote?

Encouraging students to make time for their passions in their formative years will increase their zest for learning and in turn, produce fruitful results in terms of academic success.

Junior Gretchen Highberger shared her journey in creating an ideal balance between school and extracurriculars. “My freshman year, I exhausted myself trying to get every single possible point on every single assignment. I was also heavily involved in a lot of extracurriculars, but I wasn’t really contributing as much as I would have liked to.”

Highberger continued, “Two years later, I’ve realized that I am much happier when I make time for activities I enjoy and when I learn because I want to not because I have to. The interesting thing is my grades haven’t changed at all, but I’m so much healthier without the pressure I used to put on myself to always strive for 100 percent.”

Success may be evaluated numerically by college admission officers, but grades are not always an accurate depiction of a student’s brainpower and, more importantly, willpower. Letters on a report card do not encapsulate a student’s potential to excel in environments outside of high school.

College freshman Elizabeth Pischke felt the adverse effects of the extrinsic pressure she faced in high school to earn perfect grades. “In high school, I put so much pressure on myself to get good grades because of my obsession with perfectionism and because high school grades are a big factor in applying for scholarships,” she stated.

“But college is a whole new ballgame. What I’m learning is that it’s not so much about the letter grade but how I keep myself motivated to have a bright future,” Pischke continued.

Highberger and Pischke’s sentiments are shared by many students, and their experiences are even backed by scientific evidence. Research has shown that when students are intrinsically motivated, they are more likely to reap the benefits of education and retain more knowledge.

Conditioning students to seek fulfillment outside of quantitative evaluations is a skill far more transferable beyond high school than a straight-A transcript.