Within the complex political landscape that America is today, there are few facets of life that politics does not touch. For many people, the birth of their perception of politics is at home.

But often times, the true development of people’s political views is facilitated in the classroom.

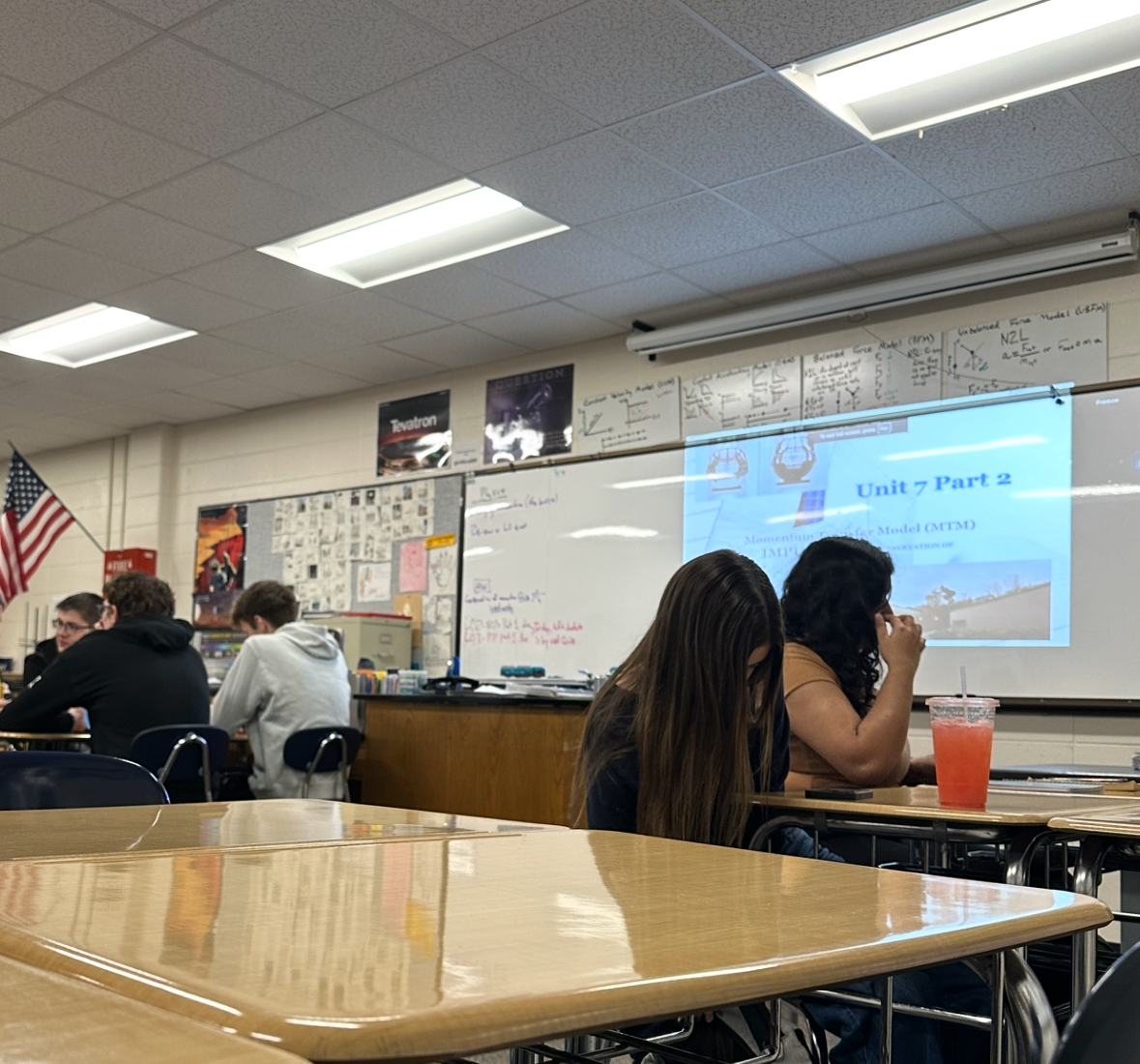

As the news cycle runs its course, it is quite often that political and ethical subjects are brought up in schools, specifically in history and English classrooms. Subjects concerning identity–whether that be race, gender or sexual orientation–can, at times, feel unavoidable in such spaces. Many teachers choose to embrace this by allowing productive discussion about these topics. However, on June 8, 2021, Iowa passed a bill that may shift the nature of these conversations completely.

Iowa House File 802 (HF 802) is summarized by Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds as “an Act providing for requirements relating to racism or sexism trainings at, and diversity and inclusion efforts by, governmental agencies and entities, school districts, and public postsecondary educational institutions.” But what exactly does this mean for public schools like PV?

Former professor and director of the University of Iowa School of Planning and Public Affairs Charles Connerly broke down what HF 802 will mean for public education in practice. He explained that although discussing racism, sexism, discrimination and oppression as a product of certain laws in the classroom is not prohibited under HF 802, conclusionary statements deeming systems in the United States inherently racist are considered violations of the law.

Connerly further questioned, “HF 802, therefore, begs the question of what is ‘systematic racism.’ If there is a system of laws that discriminate, isn’t that ‘systematic?’”

HF 802 and, on a much larger scale, the ever-changing political climate of the United States have raised questions about how difficult topics are approached in the classroom. Teachers are often tasked with the overbearing responsibility of addressing and sometimes even introducing students to complex topics like race, gender and sexual orientation–to name a few. An immense amount of pressure is placed upon teachers to address such subjects without influencing students and telling only one side of the story.

But how exactly are teachers supposed to approach bias in the classroom? How are teachers meant to teach the other side on issues of ethics? In an era where political affiliations are so heavily intertwined with morals, to what standard should educators be held?

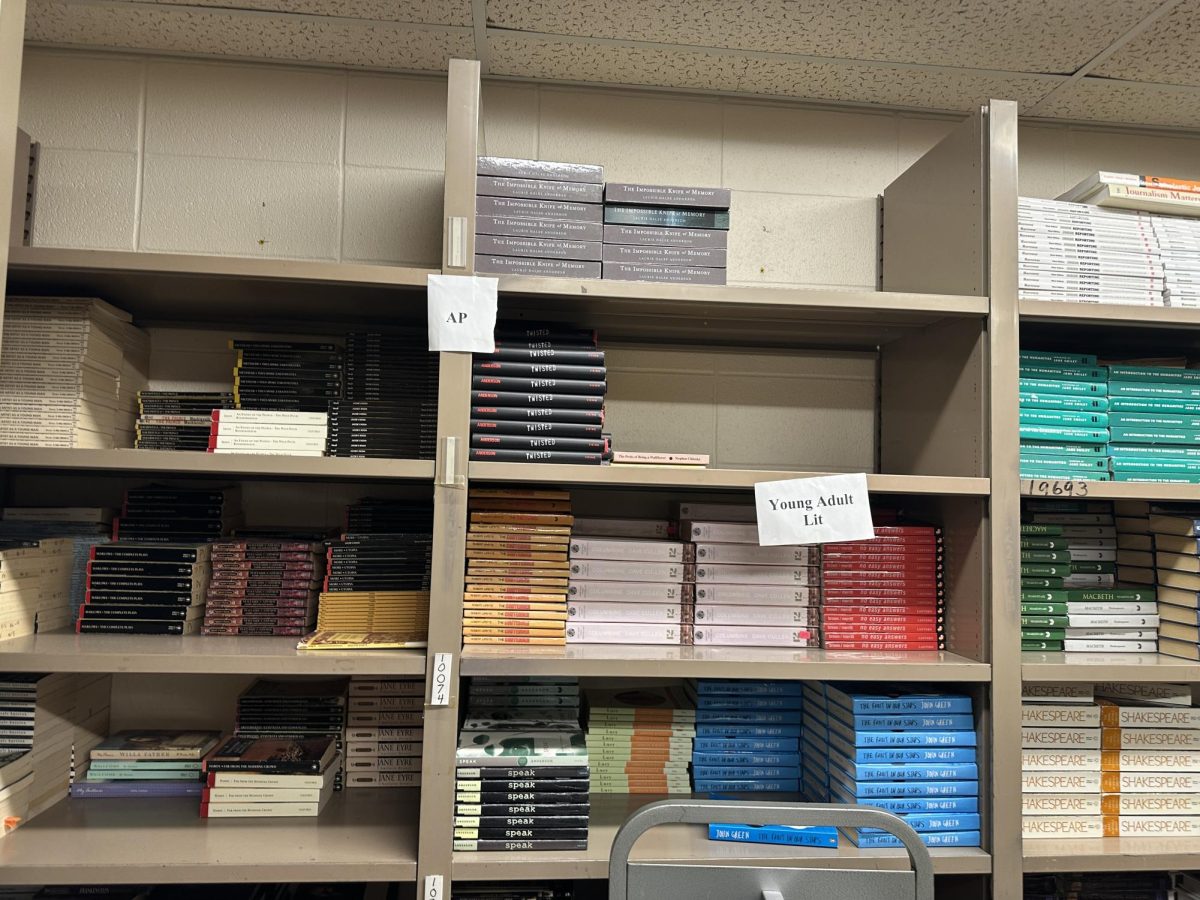

All of these questions came to a head at a series of board meetings over the summer. Several parents and students attended these meetings to condemn how certain lessons were being taught, specifically in PV’s 11th grade American Literature course. In this class, students are to read books like The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and the memoir The Color of Water by James McBride, both of which offer critiques of the American Dream and discuss the complex intersections of race and socioeconomic status.

Senior Ethan Belby detailed his perspective as having taken American Literature last year as a junior. “If we as students just spend our time in class reading books that portray an imaginary America where struggles of minorities are excluded to show a picture of fairness and equality, we miss out on an essential part of what our country is and what has led it to be in the state it is today,” he said. Students like Belby have found great value in learning about the experiences of minorities in this country by taking classes like American Literature.

However, some parents expressed concern that students were being taught to view America negatively and, further, that race is determinant of one’s success. But again, this raises further questions. What is wrong with viewing one’s country critically? If we care about the wellbeing and future of this country, should we not try to fix it? While it is not true that race is determinant of one’s ability to be successful in this country, should we not analyze the intersections of identity and affluence both today and in the past to build a better future?

English teacher Jenni Levora has also been faced with complex questions in her own classroom when teaching books like Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates and To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, both of which intensively discuss race.

In light of HF 802, she further expressed, “I’m concerned that there might be individuals with an aggressive agenda, taking little phrases or items out of context or trying to ban certain texts without even reading them. I’m going to carry on as I always have, though. I think my students know that I’m trying to help them expand their perspectives and practice critical thinking, but I’m helping them grow in terms of how to think, not what to think.”

Levora brings up an interesting point about the narrative surrounding teaching these complex issues. There is so much discussion about what educators are teaching when the question should be how they are teaching it. One primary concern from both parents and students seems to be the line between education and indoctrination, which can, at times, be blurry. However, it must be said that there is no other side to the reality of people’s lives in this country.

Time will tell how HF 802 will truly impact the nature of discussions about race, gender, sexual identity and so on in public schools in Iowa. But within the ambiguity that surrounds this issue lies one truth: just because conversations are difficult to have, does not mean that they should not be had at all. When students are made to feel uncomfortable, they are forced to think critically and question their own views. Rather than deeming this indoctrination, let us embrace the opportunity to listen to one another’s perspectives in an increasingly divided country.

Within the complex political landscape that America is today, there are few facets of life that politics does not touch. For many people, the birth of their perception of politics is at home.