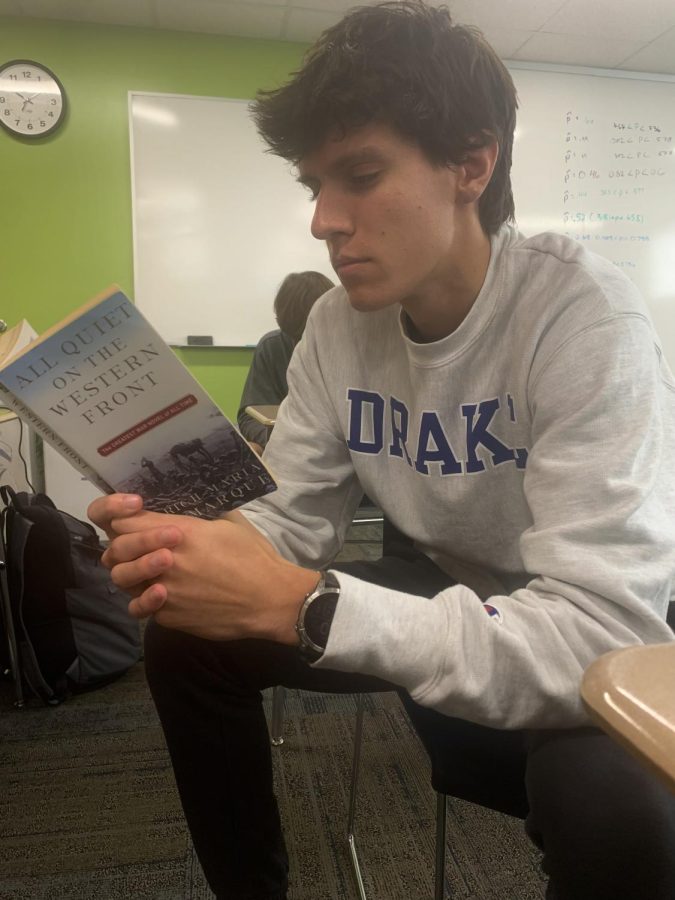

On Oct. 28 Netflix released their 2022 adaption of Erich Maria Remarque’s novel, “All Quiet on the Western Front.” This movie follows Paul Baumer, a young German boy who has fallen into the notion that fighting in war is the most honorous, glorious thing one can do.

However, these innocent views are quickly shattered. As the movie sharply switches scenes from Baumer’s life as a schoolboy to an expendable on the warfront, the brutalities of war are bluntly shown. Like Remarque’s 1928 novel that was famously banned by Hitler, this movie not once romanticizes war.

Death, death and death. As the two sides, both consisting of young, disillusioned men fight each other on behalf of some “civil” diplomats, the movie utilizes stark contrast to share just how irrational World War I seems. The generals of the time truly had no regard for the life of a soldier.

Social studies teacher Joe Youngbauer recently viewed the movie and believed it did the war justice. “The military aspect of the movie was brutal and there was just this sense to it that this was really what these people had to live through. It does a good job of showing the harsh realities of war and not once romanticizing the war,” Youngbauer stated.

In the first five minutes on the warfront, one of Baumer’s childhood friends Kammerer dies, crying, wailing to go home and wanting to see his mom in his final moments. This immediately sets the tone of the movie. A good war movie is meant to make you feel uncomfortable, since after all, it’s a movie about war, not some romance or comedy. “All Quiet on the Western Front” is not a fun watch, just like it was intended.

The movie has a recurring synth, blaring its fog horn like sound, in scenes that are calm as well as fiery. This sound is a warning to the viewers: something brutal will happen. The perpetual loss and grief of war weathers these boys, who march into the trenches as young schoolboys.

Immediately, the brutalities of war are shoved into the faces of viewers, front and center. Deaths are constant and the value of life is seemingly worthless. The movie does a great job at contrasting this, drawing parallels between the ruthless German generals and the bloodlust of the warfield.

“You get the sense of the sentiment of these nations at the time of this war. They [generals] saw war as a good thing, as if it was the glorious thing to do to fight to expand the country. The movie does a good job of showing the generals’ bloodlust, willing to sacrifice thousands of citizens to expand the country,” Younbauer continued.

This movie is not the first adaptation of the book though. With the book published in 1928, the first film adaption was made in 1930, a mere 12 years after World War 1. The story proved to be so moving that Hitler banned it, citing it made Germans look weak and that it discouraged war.

An interesting distinction between the two world wars is reducing down and thinking about why they were fought. “World War 2 was fought because all of these countries came together to defeat an expanding evil of the Nazis, while World War 1 was just because these generals had an imperialistic mindset, wanting to fight in war to try and benefit themselves,” Youngbauer concluded.

This distinction brings another element to the irrationality of these deaths. Understanding that all the casualties could’ve been easily avoided makes the movie all the more emotional.

Netflix excelled in showcasing the reasoning behind the war. The war seems pointless. With World War II, at least the reasoning was to end the encroaching fascist Nazis, but World War I was avoidable if the countries’ leaders were less greedy.

In one scene the war generals are on a train, hoping to sign a treaty. One German general, while hundreds of miles away from the trench-warfare, insists on prolonging the war, seeing it as a purely positive thing for the country.

This shares the unsparing environment of war, where these young men are used as expendable pawns for their nations leaders.

In another scene, Baumer is stuck in the muddy pits of the war with a French soldier. As soldiers, they instinctively fight. Baumer chokes the soldier to the brink of death, and because of the shooting overhead, Baumer is stuck beside the dying French soldier in his last minutes.

The inner love that transcends war is showcasedf and Baumer— in a moving, plightful scene— tries to save the man. Unfortunately, the guy does not survive. Still unable to move, Baumer is stuck with the corpse whose blood is on his hands.

Waiting out the night, Baumer goes through the soldier’s things, learning that the guy is a shoemaker who has a wife and child back home. In this emotional scene, Baumer recognizes that he killed a man with a family sheerly because the leaders of the country told him to.

Neither of the soldiers wanted to fight, but were forced into such a situation. This was one of my favorite and most impactful scenes in the book and I am glad that they did the scene justice in the movie.

Two other scenes that were my favorites from the book were not in the movie, though. In one scene Baumer and his friends sneak out into the night, and hang out with French women. Giddy to see women and have a sliver of a normal life, they are ecstatic. Quickly, though, these still-teenage soldiers realize that they don’t fit in.

Their short adulthood has been nothing but war, and they therefore don’t know how to interact with these girls. Alienated by society, these soldiers in the most morbid sense find solace in the atrocities of war. War has weathered these young men and have killed countless of their friends, but at least they are familiar with war as opposed to living in society.

Remarque creates a wonderfully sad theme throughout the book that I thought was underdeveloped in the movie. These men have lived their entire adult life in war so that even if the war were over, they would not be able to adapt to a “normal” life.

Disappointingly, what I thought was the best scene in the novel was omitted from this adaption. In the book Baumer receives a chance to go home for a short break. He is finally back home to the love of his mother, delicious hot food and the comfort of his childhood bedroom. Despite all this, Baumer feels alienated.

Baumer is no longer the kid he was when he lived that life and he doesn’t know how to live in the quiet village homes. Baumer, although in the comfort that he had so longed for while out on the warfront, finds himself yearning to go back to the fields, back to the battle with his comrades.

The bond of brotherhood is another recurring theme Remarque wrote about that made this book so timeless. Thankfully I felt like the movie showcased this brotherhood well, scattered between the brutal depictions of war.

In one scene, Baumer and his friend Tjaden are seen walking on a silent snowy day. As they reach a quiet farm, they sneakily steal a goose, rewarding themselves with a big feast. This scene is heartwarming and shares the true bonds made. Even though there are pockets of positivity like this one, it is drowned out by the overwhelming negativities of war.

Overall, I think this movie does an excellent job at showcasing the harsh realities of war, and successfully portrays the anti-war sentiment that Remarque had so craftily penned in 1928. The cinematography was spectacular, showcasing technical brilliance while depicting such depraved settings. Within war movies this is definitely a good one, but I would say that there are better ones out there like “Saving Private Ryan,” (1998) and “Apocalypse Now” (1979).

I would recommend this movie to anybody who wants to gain some history knowledge, but definitely not to anybody who wants a light-hearted feel good movie. If you are looking for that, I would recommend Kung Fu Panda.

“All Quiet on the Western Front” (2022) can be watched exclusively on Netflix now.