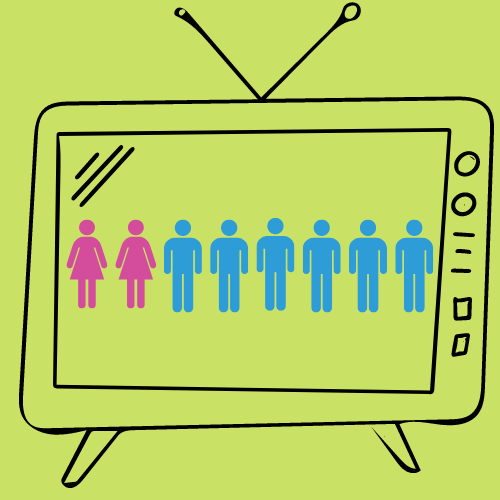

Although women have long been behind the brilliance of movie-making both on and off-screen, film has undeniably been a male-dominated industry for all of its history— 71.8% of filmmakers are men, and male actors receive, on average, twice the amount of screen time as their female counterparts.

In the early days of film, women were exclusively cast in archetypal roles: the hero’s prize, the unintelligent, love-obsessed teenager or the hypersexualized fantasy.

Produced in the early years of the sound-era in film, the female-led film “Applause” (1929) portrays women as nothing more than objects of desire.“King Kong” (1933) features protagonist Ann Darrow as a damsel in distress. Similarly, “Batman” (1966) depicts anti-hero Selina Kyle as appealing to the male gaze, evident through her sexualized costumes and outdated femme fatale archetype.

In the past decade, the entertainment industry has seen significant changes to female representation in film. An annual study conducted by USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative that tracks gender, race and ethnicity of lead characters for the 100 highest-grossing films each year reported that 41% of leads or co-leads on this list were women— a steep improvement from the single film that starred a woman the first year the study was conducted in 2007.

With the postmodernism movement, there was a push towards analyzing and questioning popular conventions that put people into one-dimensional characters—particularly women.

Now, films are filled with women who reflect the changing values of the contemporary world we currently live in. When viewing films starring female actresses like “Ocean’s 8” (2018), “Coda” (2021) and “Black Widow” (2021), it is easy for audiences to forget the fact that women didn’t just walk into these roles, but rather, they are roles that women had to fight for to be represented in.

Senior Caleb Swinney has noticed the increased representation of women in film but recognizes that there is still room for improvement. “I don’t think the film world is giving women the credit and opportunities they deserve. There are a ton of great movies right now that feature amazing female leads, but there should be more.”

Although there have been notable improvements over time in the entertainment industry, a new issue arises. Though women have seen an increase in screen time, one test is enough to reveal the misogynistic intentions behind the role: the Bechdel Test.

Coined by Alison Bechdel in 1985, the Bechdel Test is an indicator of how women are represented in film. In its simplest form, the test evaluates whether two women can have a conversation about something other than a man.

In order to pass the Bechdel Test, three criteria must be met:

- The scene must feature at least two named female characters

- The women on screen must be talking about something other than a man for more than five words

- They must appear on screen together for more than one minute

These requirements form the foundation for what has become a quick way to gauge the sexism that is prevalent in character portrayals of female characters.

Many movies touted as trailblazing feminist works fail the Bechdel Test, including “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961) and “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” (2011). Other films passed, such as “Goodfellas” (1990) and “Twilight” (2008), unexpected to audiences.

Media studies have found that there is a correlation between movies that pass the Bechdel Test and financial success. Some of the movies that passed include “Divergent” (2014) and the Oscar-nominated films “Get Out” (2017) and “Hidden Figures” (2016)— all movies that performed well in the box offices.

The point of the Bechdel test, as intended by the creator, isn’t to prove how feminist a movie is, but rather to demonstrate a systemic problem in the film world that centers media around a male perspective.

Swinney recognizes that the increased use of the Bechdel test is a step in the right direction, but that there is more work to be done. “I think the Bechdel test has created a quick way of judging whether or not a movie is considered ‘sexist’ or advantageous toward men. But I don’t think it’s a foolproof judgment for some movies. There are still movies that pass the Bechdel test that have other problematic portions that can still be considered sexist,” he continued.

Although the three-rule Bechdel Test is not a perfect indicator of feminist media, it does raise questions about how we, as viewers, consume our movies.