From slavery to segregation, America’s past stains still linger, tainting the very foundation of our healthcare system and leaving marginalized communities in a constant state of fear and distrust. America’s racist history continues to bleed into all facets of life, systemically harming black and brown communities because of a lack of trust in the healthcare system. This mistrust has adverse effects, as individuals are forced to question the quality of care they may receive.

Clinical trials in particular pose a deadly conundrum for many minority participants.

Ethical clinical trials heavily rely on a strong patient-provider relationship, based on trust and the idea that the patient is the expert on their condition. They often test pharmaceuticals and treatments for additional side effects, which can differ based on slight physiological differences.

Participants need to be able to trust their medical providers, but, unfortunately, that trust is often void for participants of color because of the long history of professionals ignoring their concerns and symptoms.

In 1932, the Public Health Service ran a medical study which studied syphilis in black men. Without their consent, 600 Alabama men were used to study the progression of syphilis. Despite the fact penicillin was the recommended treatment, researchers administered placebos, allowing the disease to spread further within the community. The so-called “participants” were never given any information about the possible treatment. Instead, the medical professionals lied about the care the men needed and were receiving.

The physical repercussions were devastating, as nearly 130 people died, but the social repercussions were far worse.

Nearly 100 years after the experiment, medical mistrust in the black community continues to prevent people from trusting their medical professionals for fear of being lied to.

When conducting clinical trials, patient-provider trust is extremely important, as it can mean the difference between life and death.

Clinical trials are conducted to test the efficiency and possible adverse effects of treatments. With any clinical trial, there is some risk being taken as these drugs and treatments are new to the market. Open communication regarding patient symptoms and concerns is essential for accurate data, but also for patients’ peace of mind. Participants need to be able to trust that their needs and symptoms will be heard, and that their provider will act according to their best interest.

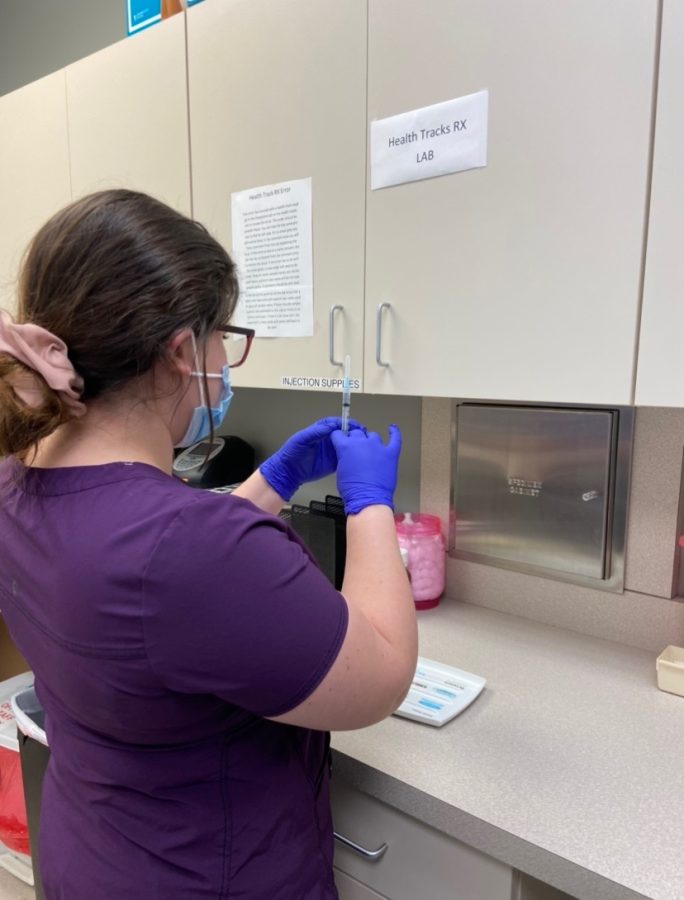

Ruby Hussain, a physician and clinical trial coordinator, works to foster a strong relationship with her patients. “It’s very important that patients trust you as a doctor. [Clinical trials] rely on your patients … [to] follow protocol criteria to collect accurate data for the trial,” she said. Hussain ensures that she has a strong professional relationship with her patients by keeping open communication with them and accommodating for their trial visits. She also ensures that her clinic is a safe space for her patients and trial participants to ask their questions and receive honest answers.

Despite efforts like Hussain’s, many patients still feel deterred by systemic racism in America’s healthcare industry, refusing to take the risk of depending on a doctor’s care any more than they need to. As a result, a majority of clinical trial participants end up being white males, causing large discrepancies in the research being conducted.

Junior Maira Dar sees diverse clinical research as essential to equitable healthcare. “Of course with diseases like sickle cell anemia and diabetes, there are certain populations that are more affected, so race and ethnicity definitely play a part there,” she comments.

Pharmaceuticals and treatments have different effects on the human body for a multitude of reasons, including age, genetics, gender, race and ethnicity. The Health Policy Committee from the American Thoracic Society published a paper regarding inequities in the quality and quantity of healthcare received by minority communities. Their findings stated that current research suggests a significant difference in the effectiveness of clinically important drugs based on differences in racial and ethnic groups in the metabolism, clinical effectiveness and side-effects of the drugs.

Front-line asthma drug albuterol is an unfortunate example of inaccurate research caused by a homogenous study pool. The drug is administered through an inhaler, often to children. Asthma is most prevalent in children of African American and Puerto Rican descent, with the mortality rate being four to five times that of Mexican children.

Yet African American and Puerto Rican children have the lowest response to the medication.

A study published by the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine found that there were genetic variants associated with the reduced response.

Dar and her younger brother have both been on albuterol in the past. She believes access to effective treatment is a patient right. “Asthma is a scary disease, and if it’s bad enough it can be life threatening. Albuterol is usually given in more severe cases, so those kids must have really needed it. They [Clinical Trial Researchers] definitely should have done more research to ensure that albuterol is an appropriate medication for everyone,” she continues.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease in children. Many parents trust the medication being administered to their children. But the research backing this drug is faulty, as a direct result of homogenous clinical trials. A lack of African American and Puerto Rican subjects in the trial resulted in the faulty conclusion that albuterol is a good treatment for everyone. If researchers had checked all of their bases to begin with, many minority children would have better access to adequate treatment.

Hussain also recognizes the harmful effects of excluding racial and ethnic minorities from clinical trials. “The more research we do, the more we realize that your race and ethnicity can have effects on your response to drugs and treatment.” she continues. Hussian also comments on the popularity of her clinic as a research site because of the diverse surrounding population, and her status as a physician of color. She believes, despite current efforts, there is still work to be done on a larger scale.

Homogeneity within clinical trials is a direct result of America’s racist past. Many minority patients are unable to trust their medical professionals to adequately do their jobs because of this incredibly racist history. Until America confronts its discriminatory healthcare history and takes steps to promote diversity in clinical trials, minority patients will continue to suffer from inadequate care.