In everyday speech, most people don’t consider the origins of the phrases they use. When terms such as “warpath”, “black sheep” and “killing two birds with one stone” are uttered, the speaker usually means them innocently, without regarding whether they might be causing damage.

In hopes of combatting this accidental oblivion, Stanford University has released a list of harmful language which should be eliminated from formal use. Though their intentions may have been genuine, the list has sparked questions and criticism regarding the real effectiveness a list like this could have in our fragmented society.

The Stanford List was published in mid December of 2022 and garnered global attention almost immediately. The list covers 10 categories: ableism, ageism, colonialism, cultural appropriation, gendered language, imprecise language, racism and violence, making up over 100 total phrases to be avoided.

Though the institution’s goal of replacing words with damaging origins was honorable, their actions were less effective than they might have hoped. People are naturally hesitant to any major change, especially when they feel like it’s being forced on them, and they responded to the list like they would any other set of regulations: with apprehension and a critical eye.

Words like “dumb” and “manmade” are so immersed in our language and culture that the idea of doing away with them seems impossible, regardless of their history. For people to effectively eradicate this terminology would take a widespread effort by institutions and individuals alike. Junior Pratima Khatri attributes most people’s knowledge of the list to its widespread mockery, “The only reason why [most people] know about it is because people make fun of it,” she said

Khatri understands why the list was made, but questions some of the words on it. “There’s a difference between words with bad connotations and words that are offensive. The list reads to me as a bunch of people who don’t fit under said categories [minorities] trying to guess what would offend people… in other words, it’s an overcorrection,” Khatri explained.

Amid the criticism that quickly ensued, Stanford eventually abandoned the initiative in early January. Their intentions were commendable, especially being one of the only major universities to publicly take action against discrimination. Regardless of their success, taking a stand is at least the beginning of combating racism.

Junior Keira Bowman recognizes the list’s potential to affect change. “Changing language allows all people to feel safer in public places. It may not change the societal structures that promote these things, but it is a very important start,” she shared.

Even if this list became integrated into our society, what would be gained? Unless people truly understand the gravity of their words and begin to treat others with empathy, the problems will endure. It isn’t enough to avoid a slur if you continue to discriminate against marginalized groups, and it isn’t enough to eliminate language if the belief systems that perpetuate hate still exist.

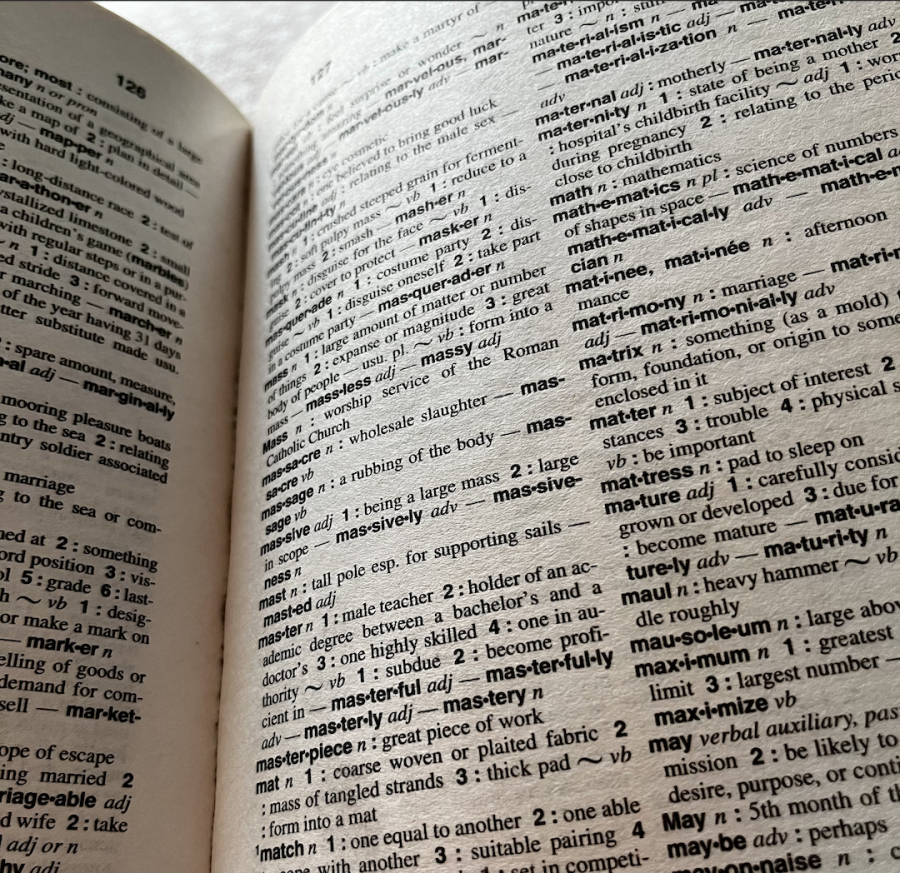

By placing focus on words themselves, the larger societal issues are ignored. While we discuss whether the terms “master” and “mastery” are offensive due to their roots in slavery, racially based hate crimes persist. When we talk about the violence insinuated by “give it a shot,” gun violence is at a record high. Every moment spent arguing about “straight” versus “heterosexual,” bills are being passed across the country to censor LGBTQ+ education.

To put it simply, the Stanford List falls short of meaningful activism. Intentional speech, though powerful, really only has any substance among those who choose to be inclusive and thoughtful— it is not powerful enough to successfully break down deeply embedded systems of hate, oppression, and ignorance. The ways people speak are reflective of their feelings and surroundings. Societal change needs to come first— only then will language follow.