More than half a century has passed since astronauts landed on the moon for the last time. Two years short of the 50-year anniversary of the 1969 moon landing, on Dec. 11, 2017, former President Donald Trump signed Space Policy Directive 1 after numerous blocks and delays during Obama’s presidency. This policy called for NASA administrators to lead a program of manned missions to the Moon, followed by missions to Mars, alongside commercial and international partners. In May of 2019, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced Artemis, the new program to send astronauts to the lunar surface.

With the initiation of Artemis, many are left wondering why NASA wants to go back to the Moon. One of the main reasons is to test the logistics and challenges of sending astronauts to another planet. The Artemis program acts as a test flight for the real challenge: sending humans to Mars.

Another reason to go to the Moon is to study ice deposits in the lunar craters. The lunar ice serves two purposes: to help better date the solar system and, potentially, create permanent bases. If the ice can be turned into oxygen, drinking water or spacecraft fuel, then stations could be established on the Moon.

On Nov. 16, 2022, Artemis I, NASA’s first stage of the Artemis program, launched from the Kennedy Space Center. The new Space Launch System rocket (SLS) sent the empty spacecraft Orion on its first trip around the moon and back to Earth. The Orion splashed down on Dec. 11, 2022 in the Pacific Ocean after traveling 1.4 million miles. The goal of this unmanned mission was to collect information about the landing zones on the Moon and to prove the Orion is capable of a lunar mission.

The Artemis II mission is set to launch in Nov. 2024; the 10-day mission will include numerous tests in Earth’s orbit. After the tests are concluded, the Orion will be sent into a free-return trajectory to and around the moon, following a similar path to Artemis 1.

This past week, NASA announced the four astronauts that are going to man the Artemis II mission. The Orion will carry three American astronauts (Commander Reid Wiseman, Mission Specialist Christina Koch and Pilot Victor Glover) and one Canadian astronaut (Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen). Among these four are Christina Koch, the first woman to be assigned a lunar mission, and Victor Glover, the first black man to be assigned a lunar mission.

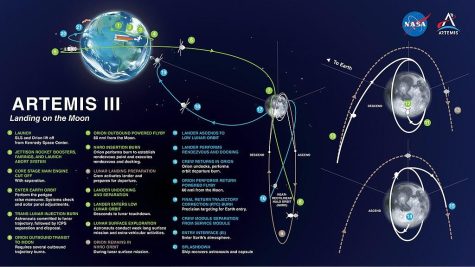

Artemis III will be the climax of the Artemis Program. The mission is set to launch as early as Dec. 2025. Artemis III will send, again, four astronauts to the moon. But, how do the astronauts get to the surface from the Orion?

The Gateway is the key to all of the future lunar missions. The Gateway plans to be the modern version of the International Space Station (ISS), but orbiting the Moon instead of Earth. The station allows the Orion and other spacecraft to dock onto it, just like the ISS. The Gateway stays in an elliptical orbit around the moon and can change its orbit to better position itself for wherever the astronauts are located on the Moon. The Gateway is set to launch in 2024, presumably after the Artemis II mission.

So, when the Orion meets the Gateway in the Moon’s orbit, it will dock, and then two astronauts will transfer to the Human Landing System (HLS) where they will descend to the lunar surface. Both astronauts will spend six and a half days on the Moon conducting Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) or in other words, spacewalks. They will take samples of lunar rocks and ice, which will be taken back to Earth and studied.

As said in the Space Policy Directive 1, NASA is to work alongside commercial and international partners. Using this, NASA selected SpaceX to design the HLS that will take the astronauts from the Orion to the lunar surface; SpaceX came back with the HLS Starship. The Starship is designed with two airlocks and is capable of being reused for multiple missions after the Artemis III.

Joining the Artemis III crew members is a lunar terrain vehicle, which would transport the crew around the moon’s surface. They also want to send a mobile habitat for astronauts that can house up to four crew members for a 45-day period.

If all goes according to plan, NASA will land astronauts on the moon in 2025, 56 years after the first moon landing. The Artemis website claims “NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon,” yet the official names for the Artemis III mission have not been released. As of now, it is unclear if Christina and Victor will be the specific astronauts landing on the Moon.

Pleasant Valley AP Physics and Astronomy teacher Ian Spangenberg expresses his excitement for the Artemis moon landings, as well as outlining the potential benefits of a base on the Moon. “If we accelerate too fast off the Earth, you can hurt your astronauts. But the slower you take off, the more fuel it takes. So the idea is to have a lot of stuff automated to go to the moon at a higher speed because you aren’t taking astronauts with [because they are already at the Moon]. And because it takes off at a higher speed, it’s cheaper to get stuff to the Moon. It is easier to take off from the Moon because it has a smaller mass than Earth,” he explains.

“So you have a whole bunch of supplies launched really fast from the Earth that goes to the Moon where you collect the materials at the station[s], build rockets, and then you can launch off easier from the Moon rather than launching from Earth,” Spangenberg continued. “But also, if something goes wrong on a Mars mission, it is a lot easier to get people back to the Moon than it is to Earth.”

Senior Ryan Stender, who enrolled in the Pleasant Valley’s Astronomy course last semester, outlines how a presence on the Moon could be a challenge. “There’s so many variables and subsequent areas of failure in space travel that are easier to work out when we’re just working with machinery [satellites, rovers, etc.], but transporting and sustaining human life in conditions we were never meant to live in makes everything so much more complicated,” he noted. “The Artemis missions will help us determine these problems in a scenario that is relatively easier to control, since the moon is so much closer than Mars.”

The Artemis program is only a stepping stone in the grand scheme of other planetary inhabitations. Regardless, the Artemis missions demonstrate NASA’s capabilities to bring together the United States and other commercial enterprises for a common goal, as well as setting up the framework for future missions to Mars.