Student experience

As students walk into their first day of school, they feel a mix of anxiety, excitement and confusion. Along with these feelings, some students are plagued with an added emotion: dread.

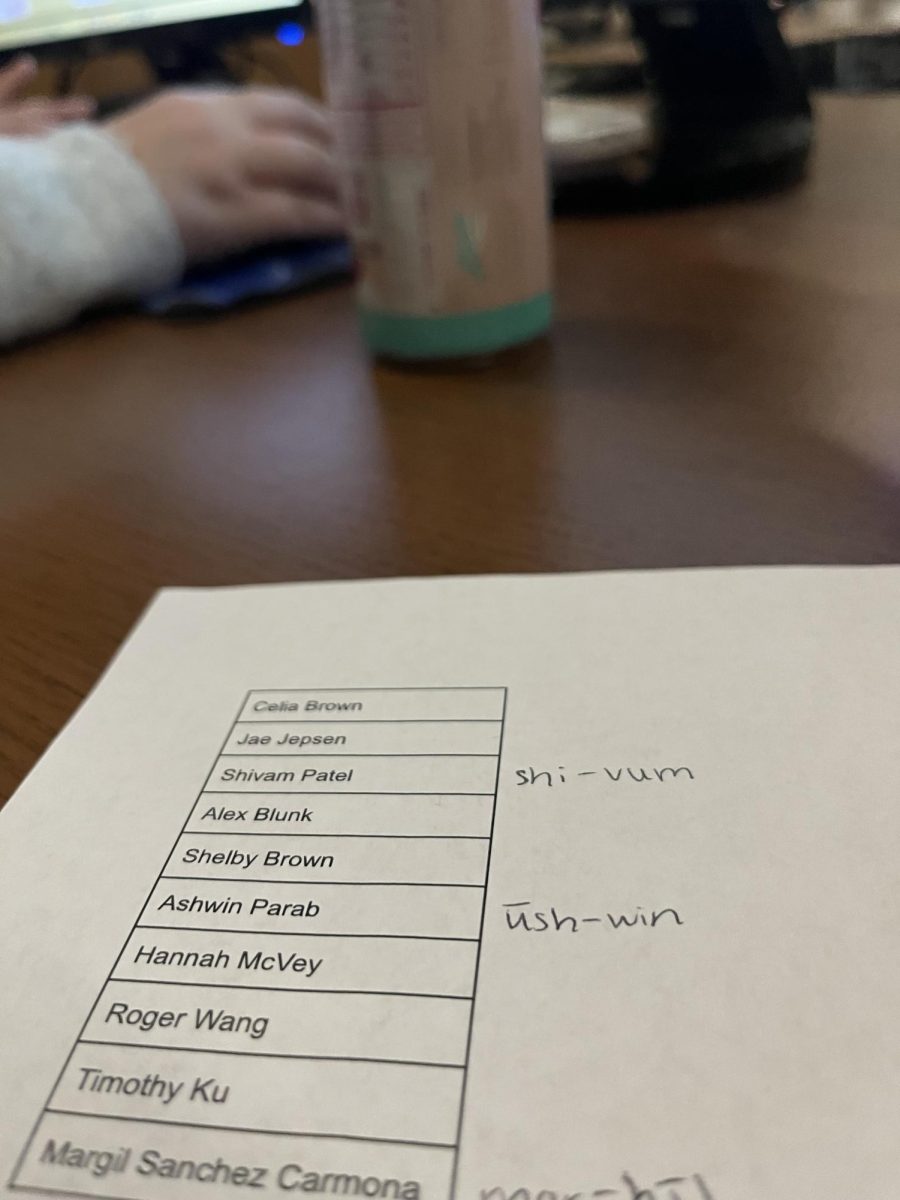

While entering each class, students with foreign names wait in apprehension for their name to be called. The teacher starts taking attendance by swiftly naming each student on their list until the inevitable pause. Each student without a stereotypical American name looks around at each other in fear, wondering who will be the first victim.

As each and every student repeats their name numerous times back to the distressed teacher, they decide to compromise on the one thing that has defined them since birth.

Teachers will often give excuses to cover up their inability to try to pronounce different names by saying “Sorry! I’m really bad at names,” or “I know I’m going to butcher this one!” But these repetitive and predictable phrases convey the opposite to students.

Even beyond the first days of school, embarrassment follows these students wherever they go.

Whether it’s having a substitute teacher in class or hearing a botched version of a name over the announcements, this frustrating practice hits hard on students’ self esteem.

Junior Ameya Menon has experienced this kind of discrimination, focusing on the teachers lack of effort. “Most of the time, teachers glance at a foreign name and immediately decide that it’s too hard to pronounce. If people attempted to say my name phonetically, it would most likely end up being right,” Menon continued. “But the fact that the name is foreign gets in peoples’ heads and all their reading skills go out the window”

When teachers properly learn and welcome diverse names, every student feels included and welcomed, which leads to better student-teacher relationships and a more productive education.

Many can also feel added insecurities from their peers, whether peers see their comments as harmless or not. Making jokes or poking fun at names is a common occurrence. Even suggesting a shorter or “easier” name can cause self-hatred towards their full name.

“A few times, people have resorted to simply saying my last name because it looks easier to say. I understand that most people have never encountered my name before, but I only have the motivation to correct them when I can tell that they respect my name and that they are really trying,” Menon expressed.

Names are not just what people go by, but rather have ties to family, culture and religion. Tampering with meaningful names alters the beautiful background behind each foreign name.

Attempted assimilation

Because of the unavoidable butchering of names by indifferent teachers and peers, some parents feel forced to abandon traditional names in favor of Western ones.

Commonly, East Asian individuals adopt English names when they arrive in the United States, and most second generation kids grow up with two names, the English name on their birth certificate and the name their parents call them.

As of 2022, racial minorities made up 26.33% of PV’s student population with 44.36% of those being Asian.

Names influence the perception of racial minorities in the US. English names suggest assimilation and acceptability in American culture. No matter how equally American, those with foreign names are far more heavily pushed into the stereotype of a perpetual foreigner who refuses to adopt the superior practices and language of their new home.

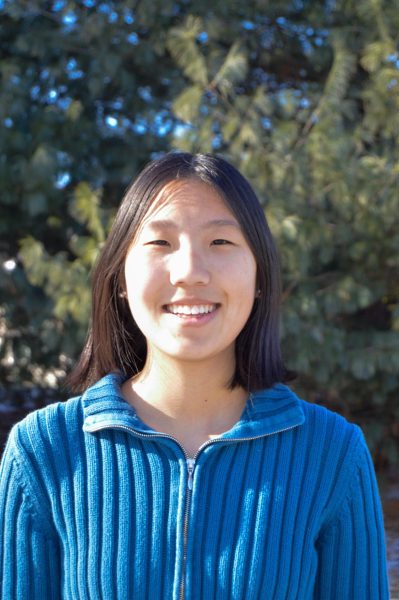

This view is projected on people despite any proof. “There have been several times where people have asked me if I’m from China or some other Asian country when they hear my name. Mind you I’ve never been to China in my life. But for [my brother] Eugene it likely doesn’t occur much since his name sounds ‘American’ or non-foreign,” explained junior Xin-Yan Chan.

American names are a purposeful attempt by parents to minimize bullying and racial microaggressions at school. Parents hope their child has less people asking where they are from and creating a spectacle of forcing them to teach words in their language.

By doing this, there is no longer a need for other students to mock their name. There is no opportunity for teachers to make a circus of pronunciation, and the teachers who don’t care to try are no longer burdened.

While this protection is justified, it can create a war of identities for second-generation Americans. Already grappling with figuring out their identity, they are left with an even larger cultural barrier to make sense of. This engenders a divide between who a person is at home and the identity they assume in public, perpetually feeling out of place in one, if not both.

For some, living and identifying with an English name more often than one of a different language can eventually result in the common feeling of being “too American” and an outsider from their own culture.

There is always a sort of balancing act between cultures and identities. “A lot of assimilation happens in immigrant families because many of them do not feel accepted, especially into the mostly white community of Iowa. I do prefer having my American name, but I have a connection to my Chinese name too because that’s the name my grandparents and extended family know me by,” shared junior Katelyn Chen.

No matter their name, students struggle with identity and microaggressions at school. Despite the best efforts to assimilate to American culture, alienation and cultural disconnect still prevail.

Microaggressions

The unreasonable mispronunciation of names is a racial microaggression. Despite the excuses teachers and peers conjure, the continuous embarrassment over weeks, months, and years signals to a student that they aren’t welcome. It tells the student that their name is their problem, excusing others from showing the basic respect of addressing them correctly.

These unpleasant experiences transcend the educational sphere. While people without stereotypically American names might think they have left the taunting and embarrassment behind after school, a new set of issues arise in their day-to-day life.

While on the job hunt, employers are 28% less likely to call back someone with an Asian name despite equal qualifications to their non foreign-named counterparts. Names that sound Black or Hispanic also face similar treatment.

Along with employment, name bias also exists in the housing market. Realtors often discriminate against people with non-European names, affecting the right of free housing.

People without Western names are alienated in social situations and disrespected by everyone around them. Left with no choice, they feel forced to abandon their heritage, trading their true identity in hopes of a shot at equality.

Shannon Korczak • Nov 21, 2023 at 12:29 pm

Fantastic piece! It seems that meaningful change could be brought about with relatively minimal effort. Awesome job bringing attention to this issue!

Nikhita Nallu • Nov 19, 2023 at 6:16 pm

Great Article! It’s unfortunate to see that even outside of the sphere of post-secondary education microaggressions occur, especially in “professional settings”.