In the opening scene of “A Quiet Place,” a family tiptoes through the ruins of a supermarket.

Their silence is deafening. Around them, fluttering newspapers hint at a world ravaged by super-hearing monsters, their headlines screaming out the secret to survive: “It’s sound!” It’s this same life-saving silence, though, that threatens to tear this family apart – the silence of grief, of doubt, of things left unspoken.

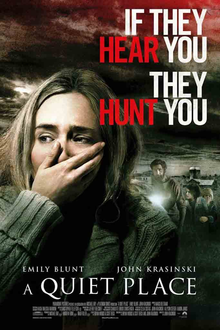

While true emotional resonance can’t reasonably be expected from a blood-and-guts horror movie, “A Quiet Place” packs a punch, with stellar performances from both actor-director John Krasinski and rising star Millicent Simmonds, watertight writing and small reminders of a world long lost that tug at the heart: a toy rocket, a game of Monopoly.

Unable to speak above a whisper, the actors rely on visual cues to emote, and the results are surprisingly rewarding; the silent chemistry between Emily Blunt and Krasinski is almost palpable, and each facial expression, be it of joy or horror, is a study in raw human emotion. The dreamy countryside setting is an expressive character in itself – colored by sunlight and a drifting pre-Raphaelite softness, it is brilliantly at odds with the horror lurking in its forests.

And so the moving pieces of “A Quiet Place” are put in place: Family dances around questions of guilt and love and blame. Farmscape dreams on. Tragedy strikes, dredging all that darkness up to the surface.

When “A Quiet Place” finally releases that darkness – both literal and metaphorical – it is terrifying. As the title suggests, the film deftly uses sound and its absence to ratchet up the tension, forcing viewers to pay attention to every breath, every footstep, every whisper of wind and sending them flying from their seats when things get loud.

The monsters, though grotesque, aren’t the scary part – it’s a character trying not to scream as she steps on a nail, or in perhaps what is the scariest part of the movie, the agonizing moments before an old man lets out a wail of grief. Underneath that is the fear of an even deeper quiet: a daughter’s belief that her communication-averse father does not love her, a mother’s surety that she is in some way responsible for the death of her son.

In other words, the true horror in “A Quiet Place” is the moments when silence becomes too much to bear.

It’s worth mentioning that even with such universal themes, the film feels surprisingly local. Some of its tensest moments make use of uniquely Midwestern fears – the eeriness of a cornfield at night, the suffocating terror of death in a silo. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that its two top writers are both from Bettendorf, Iowa.

Bryon Woods and Scott Beck first conceptualized the movie while at a nonverbal communications class at the University of Iowa; both agree that the college itself and the general atmosphere of the state’s rural places were critical influences. In an interview at IowaNow, Woods said, “‘A Quiet Place’ was always written with cornfields and corn silos and that farmland that we grew up in that felt really idyllic, and we wanted to make that scary within the confines of that specific movie.”

Clarifying the sources the duo drew from, Beck said, “We thought that you could marry a Buster Keaton-esque silent film kind of genre [seen during class] with with horror or thriller, that it could also be really suspenseful.”

In celebration of the film’s success, Woods and Beck came back to the Quad Cities to watch the opening night premiere at Rave on 53rd. They say that the supportive response they received from both individual Quad Citians and larger institutions like the Putnam, which allowed them to screen homemade feature films in high school, helped them pursue their dream of filmmaking.

“For us, this was the best place imaginable to start making movies when we were kids. To come back to that community that supported us is the highlight of all of this,” said Beck after the premiere. “We absolutely believe this is the Quad Cities’ movie, too.”

For all its heavy themes and grim-dark survivalism, “A Quiet Place” reflects that passionate yet playful time of experiment in the Quad Cities – camera angles bounce effortlessly from closeups to dizzying downshots, background props from baskets to footstep-muffling sand paths are rendered in loving detail, and the ending scene feels both like a challenge and a much needed burst of hope.

It is by no means perfect; plot holes abound, and the score is more impediment than music. But much as its characters learn to protect themselves and eventually forgive, it is a story of becoming. One can tell that Beck and Woods had fun writing this movie. And as millions have already found, you’ll have fun watching it, too.