The year is 2020, but somehow, anti-lynching legislation was passed in the House of Representatives just two weeks ago. If passed by the Senate and signed by President Donald Trump, it will have taken 120 years for the U.S. to pass an anti-lynching law since a similar bill was first proposed. The news has evoked joy, confusion, sadness and even anger.

And all of these feelings are warranted.

To be clear, the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act (H.R.35) does not make lynching a federal crime or even a hate crime. Rather, it adds new criteria for what constitutes as lynching and details the penalties. When the bill was originally introduced to the House of Representatives, it was intended to specify lynching as a hate crime. However, it was amended days before voting and is now a “bill to amend title 18, United States Code, to specify lynching as a deprivation of civil rights, and for other purposes.”

Lynching as a hate crime isn’t mentioned.

Under the amended edition, the bill also states, “Whoever conspires with another person to violate section 245, 247, or 249 of [title 18] or section 901 of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (42 U.S.C. 3631) shall be punished in the same manner as a completed violation of such section, except that if the maximum term of imprisonment for such completed violation is less than 10 years, the person may be imprisoned for not more than 10 years.”

The new act specifically targets conspirators in a lynching or other crime, since lynchings were commonly done by groups instead of individuals. As stated in the quote, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 and section 249 of title 18 in the US Code already address hate crimes — without specifying different types — as federal offenses.

So while “anti-lynching” is in the name, H.R.35 doesn’t change much in terms of challenging the crime on a federal level. It mainly serves as an apology from the United States government to African-Americans for not passing an anti-lynching bill when it was needed.

A young nation’s long history of lynching

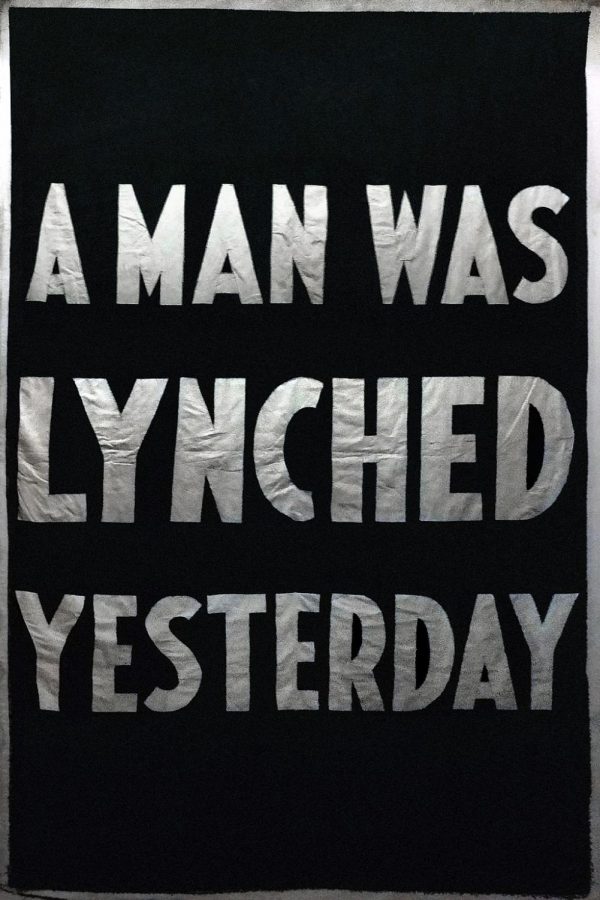

“A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” — these were the words emblazoned on a flag raised by the NAACP every known time an African American was killed by a mob.

The flag was flown far too often; over 4000 lynchings of African Americans were recorded from 1877 to 1950 in the South alone. These acts of terrorism were not done in the dead of night; they were public spectacles that even small children attended. People often boasted their participation in a lynching by having their picture taken (graphic warning: here are examples). These pictures were often sent out as postcards. Victims’ body parts were collected as souvenirs as well.

This may sound like a description of some dystopian fiction novel or, at best, something that could only have happened a time long ago. But many Americans alive today have lived through the times when lynchings were commonplace. A child present at a lynching in the 1940s would be less than 90 years old today.

A work in progress

PVHS history teacher Joe Youngbauer believes H.R.35 represents a small victory over the hate plaguing the United States. “This legislation works to fight against the symbols of lynching that are still periodically seen in our society today,” Youngbauer said. “Beyond just lynching, this law fights back against other hate crimes that exist today, too.”

While many share Youngbauer’s views, there are some — such as U.S. Representative Justin Amash — who oppose H.R.35. Amash was one of four representatives who voted “no” on the act. Many people were quick to attack Amash, labeling him as a racist, slack-jawed idiot, member of the Confederacy and more. At first glance, voting against an act with “anti-lynching” in the name does seem counterintuitive, stupid or even racist. But Amash brought up valid points.

“H.R.35 bans activities that are already illegal under federal law,” Amash tweeted. “It’s based on the unconstitutional federalization of criminal punishment, which is a threat to civil liberties and civil rights — particularly for people of color.”

Amash further explained his stance, saying since lynching was already a federal and hate crime, the new act was unnecessary and potentially harmful. He described what he believes are the risks of the federalization of criminal law. “Creating federal crimes for matters that are normally handled by the state obscures which government — federal or state — is responsible for investigating and prosecuting the crime, and it gives power to unelected federal officials whom voters can’t directly hold accountable,” Amash continued.

He also explained why he thinks the law could inadvertently harm people of color. “The bill’s main effect is to enhance max sentences for [conspiratory] crimes, up to the death penalty in some cases — a punishment that millions of Americans, myself included, oppose. To the extent there are unjust sentences, it’s likely that people of color will disproportionately suffer,” Amash later tweeted.

Amash’s integrity and willingness to stand by his values is admirable; he believes all laws should be judged based on their real world impact — not just what they seem to represent.

Whether or not his arguments were enough to justify voting against such a symbolically monumental act is the question. “There certainly are instances when our government and elected officials must work to protect the rights of states,” Youngbauer commented. “I don’t think this particular piece of legislation is the place to make that stand.”

On most occasions one would be considered morally bankrupt to vote for a bill they didn’t agree with; but for many Americans, it was the only acceptable thing for the representatives to do in this case. Anti-lynching bills have a disturbing history in Congress; acts of a simlilar nature have been rejected almost 200 times since 1900, reflecting the deep racist roots of the United States. Voting against this bill — after decades of earlier congressmen voting “no” for mostly bigoted reasons — may feel like a slap in the face to everyone affected.

It is true, however, that the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act has little more than symbolic value today. As stated previously, there have been many federal laws which have already condemned all hate crimes, lynching included.

Combined with the fact that lynchings are (hopefully) a thing of the past, this shows H.R.35 served mostly as an emblematic gesture — a small apology to all the black people who have suffered from their government’s lack of help.

If enacted when it was first proposed — or even 50 years after — making lynching a federal crime would have brought justice to the victims by convicting the murderers and deterred many of these mobs from killing. Southern states at the time would turn a blind eye to the lynchings or even go as far as acquitting murderers with an all-white jury; the federal government stepping in would have helped end this.

But the past, unfortunately, cannot be rewritten.

Jack Young • Mar 13, 2020 at 9:28 am

This was beautifully written TJ! – Jack

Best Copy Editor out there. – Sherm