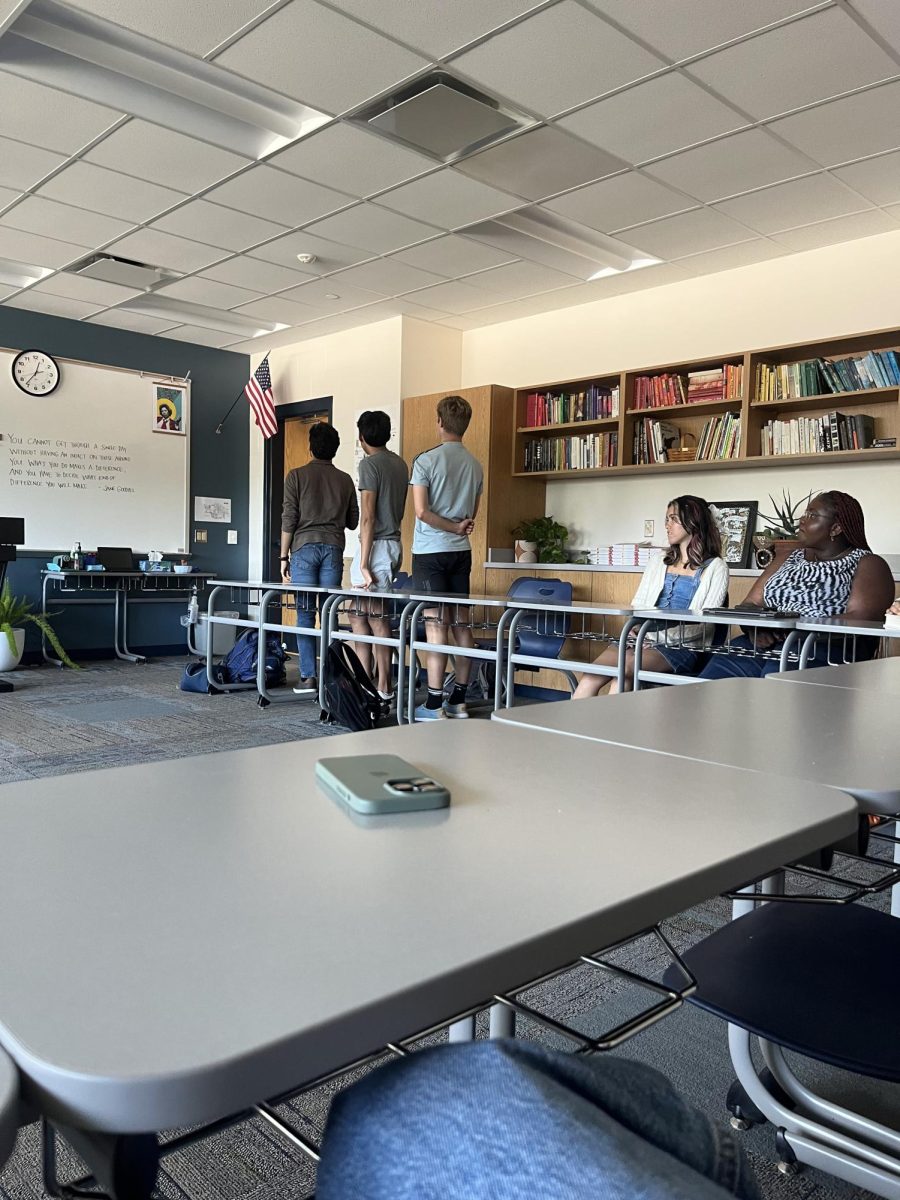

Every morning, the pledge of Allegiance echoes through the classrooms of Pleasant Valley High School. Students rise from their seats, hand on chest, and declare their “allegiance to the flag.”

The tradition officially began in 1923 when the National Americanism Commission incorporated a salute to the American flag into its flag code. The initial draft dates back to 1892 when Francis Bellamy wrote the first section of the pledge for the National North Columbia Celebration – a national celebration for Columbus’ discovery of North America.

Bellamy’s draft gained traction from patriots around the country who feared the influx of immigrants from Europe. They believed that a commemoration of national unity and loyalty to the country was crucial to maintain their sense of national identity.

Shortly thereafter, school districts unofficially integrated the pledge of allegiance into their daily routine to instill loyalty within students.

Nearly 100 years later, students have begun to reject the tradition, citing conflicting ideologies with the pledge and the government it represents. One of the most important sections of the pledge states the flag is representative of a national that is “indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” It suggests that all Americans are entitled to equal protection under the law; recent political trends seem to suggest the opposite.

In 2022, the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade stripped women of their personal autonomy. Iowa’s recent bill pertaining to transgender civil rights – the first bill of its kind in the country – deprived transgender individuals of any protections of civil rights.

Given the increasing normalcy of such reversals, select students believe that they do not have the responsibility to stand. “I personally sit down during the pledge of allegiance because it is a way for me to show that I don’t agree with many recent actions and decisions taken by our government,” Maya Vargas explained. “I don’t believe America truly gives liberty and justice to all.”

In 2020, feelings of extreme pride for the US hit a record low amongst Americans: 63% of Americans felt that they were extremely proud of their country – down from 91% in 2004. A similar pattern is evident in the amount of people who believe patriotism is important to American culture: 38% of respondents agreed with the statement compared to 70% in 1998.

Yet most students, regardless of whether or not they utter the words, always stand when the time arises. To junior Jayla Bischoff, it is not necessarily a reflection of her political ideologies, but an effort to respect those that have come before her. “It represents so much more than the words spoken. By standing, you are showing honor to your country and everyone that has sacrificed so much to make it a great place to live,” Bischoff commented.

Bischoff’s beliefs stem from the principle that the pledge is a representation of the history of the United States and everything that it has endured.

Some of the most important pillars upon which the Pledge of Allegiance was built, however, do not stem from a desire to represent history. In 1954, Harry Truman inserted into the pledge an allusion to God for the sole purpose of brandishing the United States’ practice of religion.

The 1950s constantly exacerbated feelings of distrust amongst people due to the increasing pressures of the Cold War and the Red Scare. The inclusion of religion was a signal to other countries that the US was different from the communists. It amplified their moral sense of superiority over countries who they believed lacked religious morals.

Even when the pledge contained no allusions to god, it was still implemented to assert loyalty onto citizens, rather than to celebrate a successful past. One could even argue that its dissemination into school classrooms stemmed from feelings of hatred against immigrants, given the desire from the “know nothing” party and other anti-immigrant groups to reject immigrants and preserve American culture.

Since the inclusion of God in the pledge of Allegiance, students and parents alike have echoed their concerns for its lack of religious inclusion. Most recently, the 2004 Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow challenged such inclusion on the grounds that it violated the students’ right to freedom of religion.

It reached the Supreme Court where they sided with the school district, not because the pledge itself was constitutional, but because Newdow did not have proper custody of the child for whom she brought the case.

A similar case ruled that the wording was constitutional because students have the right to remain seated.

For everyone who chooses to exercise their enumerated right by either standing up or sitting down, the pledge of allegiance is representative of something different. “I personally don’t really care,” sophomore Luca Botarelli said. “You can stand if you want. You can sit down if you want; you have the right to do both.”