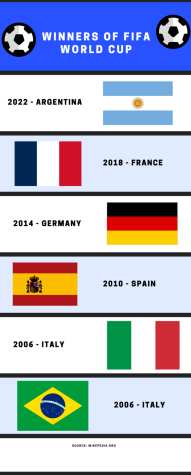

Though the Olympics includes a soccer competition, it is not the premier soccer competition of the world. The FIFA World Cup held every four years showcases the world’s 32 best soccer teams and is considered to be the top event of the sport. However, unlike many sports in the Olympics, the US has never dominated the World Cup.

Rather, the World Cup has been dominated by teams like Brazil, Germany,and Italy, who have won five, four, and four titles respectively. Despite the fact that soccer is overshadowed by sports like football and basketball, the US is curiously absent from the record books.

Contrary to what it might seem, the US’ lack of success is not all due to a lack of talent. Although soccer has become relatively popular in the US, it has had a less than perfect system of attracting the best players to the US’ professional league, Major League Soccer or to the US national team.

Most foreign soccer leagues maintain lower-level soccer teams and leagues in order to sustain interest and talent to feed their elite teams. This has elevated the top-level soccer talent in those countries, something that the US did not have until recently.

Senior Nirmal Alla who plays soccer for the Spartans, commented on the struggling structure. “If you look at countries like Spain or England, they have effective programs that are able to locate talent and supply that talent with the resources needed to be successful. I think this is the major downfall of US soccer and why they have not been as competitive in past years,” Alla stated.

A deeper analysis into the floundering US soccer system is explored in a book by George Dohrmann, “Switching Fields: Inside the Fight to Remake Men’s Soccer in the US,” where he says the American Youth Soccer Organization’s problems arose when the league was first organized in 1962. It was a system of suburban teams run mostly by fathers of players, leaving the teams with little quality leadership. It led to a, “hoof-it-up, physical, run-a-lot style of play. There’s a lack of awareness of just playing the game,” Dohrmann wrote.

Dohrman’s premise of the book is that US soccer is now transforming. With the development of Major League Soccer’s “development academies, similar to minor league teams in baseball,” the US started taking steps in the right direction. This system of chasing good players and allowing them to play like foreign networks was a welcome change. Last year, MLS revealed a new development league, meant to “complete the professional pathway between our academies and the MLS teams,” said the MLS president Mark Abbott.

Freshman Ethan Chang,who plays for a club soccer team, believes these changes are having a positive effect on American soccer. “I think youth soccer is growing in the US with programs like MLS Next, ODP, and ECNL clubs to help breed the next generation of successful soccer players. [in the past] you rarely saw many American players in the top leagues, but now there is quite an increase in American players in top leagues.”

US soccer’s efforts to develop its lower leagues is not only a win for US soccer, but also a win for youth who would otherwise struggle to be able to play. The New York Post interviewed Dohrman on his book and commented on the previous system, “Travel club teams with costly joining fees sprang up, further excluding poor, inner city kids and more insular Hispanic communities. The ‘pay to play’ model, as it was known, essentially whittled down what should have been an abundant talent pool.” New development programs are a step away from that state of US soccer, and a step in the right direction.

As US soccer continues to develop, hopefully we will not only see a growth in the US’ presence in international soccer, but also a growth in youth soccer where there has previously been no space.