The initial proposal

Around the halls of Pleasant Valley High School, conversations about the future of late work policies have been ruminating. At the forefront of these ongoing discussions is a proposed initiative: the removal of academic penalties for late work.

This new policy, championed by Principal Darren Erickson, has been proposed in an attempt to “separate behavior from learning because the two are mutually exclusive,” as Erickson described.

However, the details pertaining to what exactly this separation of academics and behavior will truly look like in practice remains murky, leaving a bad taste in the mouths of both teachers and students alike. Who exactly will take on this responsibility? What exactly will the behavioral consequences be? What effect will this have on the educators?

An important distinction to be made with this new policy is that deadlines are not completely disappearing; it’s the consequence associated with missing a deadline that would be changing, targeting a student’s behavior rather than their grade. “My goal is to move to do as much as we can to separate the behavior of the grade. If you did 20 out of 20 work, I want to give you a 20, but I need to address the behavior and the consequences that let you know this is not okay. Deadlines matter. Responsibility matters,” Erickson stated.

As idealistic as it may sound, this new policy is bound to take a large toll on teachers. Overworked and under-compensated, teachers are already tasked with educating hundreds of students in the classroom, grading their assignments and preparing lessons. Teachers will inevitably face the brunt of the effects of this policy change, who will be required to accept assignments on a rolling basis, infringing on their already marginalized work-life balance.

The proposed behavioral consequence is synonymous with a required academic study hall, where failure to attend counts as skipping class, which would result in a referral.

In describing the behavioral consequence for a student’s late work, Erickson continued, “You’re assigned an 8th hour, I’m pulling you from study hall and assigning you to an academic study hall. Not only do I want you to do it, I make you do it or I keep urging you to get full credit for what you know, while giving behavior consequences that fit the behavior without hurting those grades.”

Erickson added, “The ones who an academic consequence doesn’t work for, we need to find a consequence that does, and the ones it does work for, we need to give an appropriate consequence and quit penalizing your grade when it’s not the grade that’s the problem, it’s because you didn’t do the assignment. It’s not about I’m going to let you do the late assignment, it’s about I’m going to make you.”

But what exactly would “making a student do it” look like? Are these truly the types of behaviors that should be fostered by a school that claims to prepare students for the future, where hand-holding is obsolete?

An effort to establish uniformity in grading policies across the board, the proposed change is already being piloted in its initial stage. “We have a building leadership team of a member of the department from each place and instructional coaches, so about 15-18 teachers who are all on board with this. This is being developed with the staff, not given to the staff,” Erickson said.

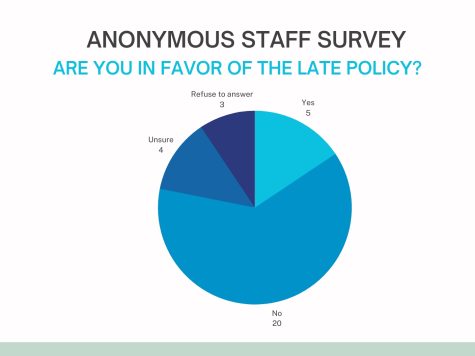

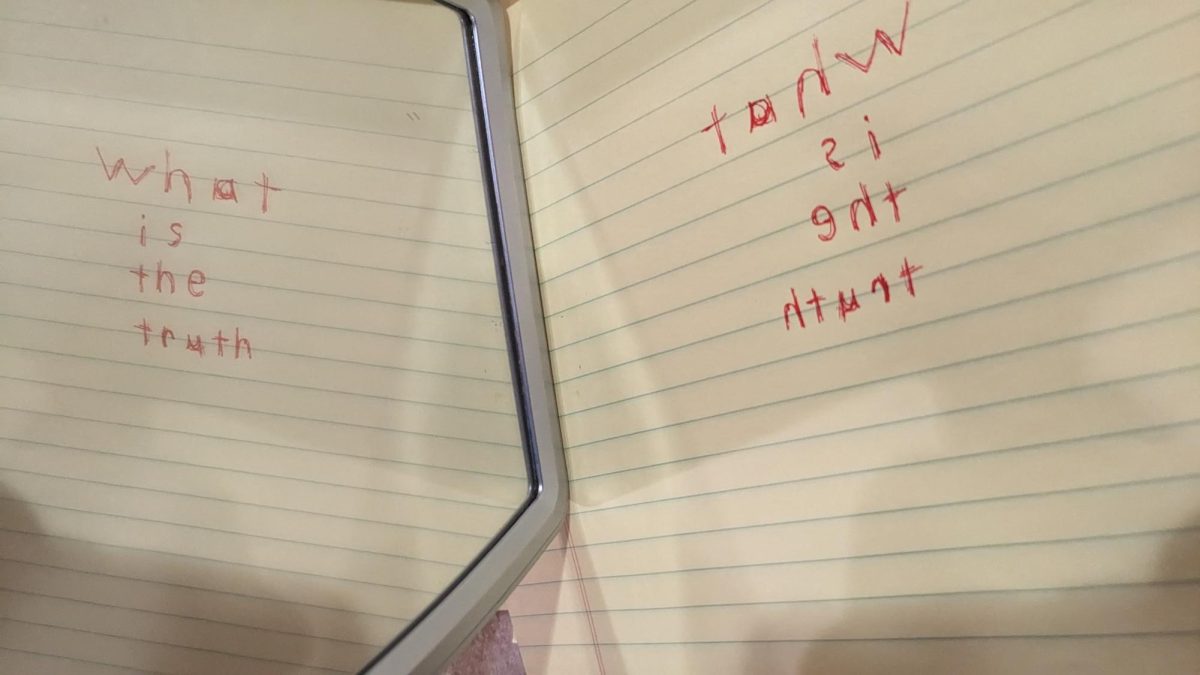

However, the results of an anonymous Shield staff conducted survey indicated quite the contrary. From the results of the random survey consisting of 32 teachers representing all departments, five were in support, 20 did not support, four were unsure and three refused to respond.

At a voluntary staff meeting on March 23, attendance was noticeably higher than usual. Among the packed library were five seniors who attended to speak on behalf of the student body. When the subject of late work policies was raised, the tension in the room became palpable, and the seniors were there to witness it unfold.

The seniors, with no stake in the game, voiced their extempore concerns about these rumored changes. After making their initial statements, they were subjected to questions from members of the faculty.

Where students found the rationale for this policy change to fall short is with the fact that the majority of teachers are not as stringent as they were made out to be. In reality, the hypothetical teacher that never accepts late work doesn’t exist—and even if they did, it is a problem that must be dealt with on an administration to teacher basis, not a school-wide mandate that affects the entire student body and faculty.

Often, with proper communication and advanced notice on the students’ part, teachers are overwhelmingly forgiving and compassionate towards their students.

The replacement of a late policy grade deduction with a glorified babysitting session takes away the professional skills that students learn from having to advocate for themselves. In the real world, employers are not responsible for hovering over their employees to make sure work gets done. This policy change would not only further burden overworked teachers, but strip away students’ intrinsic motivation and self-advocacy skills.

In college, grading policies vary by professor, and student-initiated communication between student and teacher is an expectation. If students are spoon-fed their assignments in high school and rewarded for their irresponsibility, how will they develop the skills needed to prosper in the future?

It is safe to say that until all the details are presented in front of us, the initial proposals for this change are haphazard at best, assembled with little consideration of the teachers’ best interests or setting students up for long term success.

Student motivations

With the future of academic late penalties looking hazy, what exactly would students lose if academic penalties were abolished?

Put simply, deadlines with tangible consequences create self-propelling students. The implementation of and familiarity with late penalties from earlier years builds strong skills students can rely on in the professional world. From primary school, students are trained to efficiently complete work on time while aiding teachers and faculty members by staying on course in the curriculum. Learning backed by a deadline helps structure students’ work, creating a pyramid of priority. It encourages students to accomplish goals in a stepwise manner, starting with smaller ones, then growing.

Without impactful consequences for late assignments, students would never view assignments with any opportunity cost, eliminating any initiative to complete the assignment out of self-volition. Students often time-block the hours before an assignment is due; with limited time before a deadline, students view that time as being best spent completing working to eliminate the deadline. If there is no foreseeable deadline or enforceable consequences, students neglect to do an assignment because the value of their time will rarely exceed the cost of completing the assignment.

Though this psychology seems obvious and foolproof, students still submit assignments late—a case-by-case, yet unavoidable, outcome caused by the limited number of hours in a day and natural human instinct to procrastinate. But late assignments can also emerge from a student’s system of prioritization.

With roughly one-fourth of 2023 class graduating with a 4.0+ GPA, a typical Pleasant Valley student has a rigorous schedule. Students take classes to push their skill level and are often quite busy with demanding course loads from each class. Therefore, a student must work smart, completing high-value assignments with the greatest return of knowledge and academic weight in relation to time. And in turn, they forgo the cost of not completing all the assignments, while still prioritizing what will have the greatest educational return.

The student has made this choice because it provides the best return. So does a student who pushed off completing a Spanish worksheet in lieu of studying for a high-impact calculus test the next morning truly deserve a working detention or some synonymous, time-consuming penalty?

Mandating a hard and fast period to complete assignments outside a typical school day is quite disruptive to most students’ work schedules. If there is a recurring pattern of neglecting assignments, failing to focus on academics and a blatant disregard for school, then it falls on the teacher to cultivate a relationship with the student to identify the best course of action.

This same communication is essential for all students. A simple conversation with a student on when an assignment might be submitted or if a grace period is necessary would be an easily customizable and personable approach to fixing late work for most responsible students.

But of course, schools are looking to maximize student motivation, to build independent and self-sustaining thinkers. So what are the drivers of intrinsic motivation?

Scott Geller on TEDx Talks delineated the core pillars of self-propelled motivation: self-efficacy, response efficacy, consequences and choice.

Self-efficacy is related to a simple question: “Can I do it?” Has the time, knowledge and training been supplemented? If students answer “yes” to this question, they are one step closer to becoming entirely self-motivated. When students feel prepared and confident to complete an assignment, they are more likely to indulge their time and effort. A curriculum can still challenge a student and push their bounds, but if a teacher is entirely absent in the learning process and the curriculum has no instructional aids, a student will have no incentive to even attempt an assignment they know they cannot do.

Response efficacy surrounds the idea of “will it work?” Will the behavior of completing the assignment eventually lead to the intended outcome? Whether the product be knowledge, preparedness or confidence, when a student has faith in the curriculum and their teacher’s opinion of their work, they will have all the more reason to do it.

Let us continue building success-seekers rather than failure-avoiders. — Scott Geller, TEDx Talks

“Is it worth it?” Consequence is the pillar of self-motivation which ultimately dictates whether the action is worth completing. Does the value of the assignment outweigh the associated negative consequence and merit the positive consequence? The role of schools in maintaining the integrity of this pillar is vital, whether the consequence stems from an academic or behavioral reinforcement.

Finally, most intricate, is the notion of choice. It is human nature to independently do anything when there is a feeling of self-autonomy in that choice. Though students are controlled by consequences, they have an illusion of choice under the guise of a deadline. They can choose to complete an assignment rather than receive a zero, possessing a sense of control in which students find solace. They are actively working towards positive consequences rather than passively avoiding negative consequences, freeing themselves from a feeling of control. And though this autonomy is almost entirely fabricated, the decision-making process inspires and motivates students.

Dedicate time and effort to create a curriculum which will fulfill these four pillars, making students feel confident and empowered to do worthwhile work. A structure based on rewarding achievement and hard work rather than eliminating choice and motivation for students will be infinitely more effective in boosting student participation.

Undoubtedly, this elevated curriculum and even the implementation of late policies will not have the same positive outcomes on everyone. But the student body is a bell curve. Students on one extreme will complete an assignment regardless of whether a deadline is in place. The opposing extreme of students will not do an assignment regardless of whether a deadline is in place. But most students, the peak of the bell, use deadlines to fuel their work and will benefit from a motivation-centered curriculum.

At Pleasant Valley, an institution committed to excellence and dedicated to fostering competitive spirit, let’s continue to build a community of powerful and willing students. In accordance with the words of Geller, Let us continue building success-seekers rather than failure-avoiders.

Jalen • Apr 14, 2023 at 10:04 pm

Your article does a great job explaining our current position in the principals ideal plan. It gives us insight to what might happen or what might be implemented in the future. It was also great how you showed his reasoning and came back with ways this might go wrong.